By Stefanie Benjamin, University of Tennessee

When you hear the name Jack Daniel, whiskey probably comes to mind.

But what about the name Nathan “Uncle Nearest” Green?

In 2016, The New York Times published a story about the distiller’s “hidden ingredient” – “help from a slave.” In the article, the brand officially acknowledged that an enslaved man, Nearest Green, taught Jack Daniel how to make whiskey. Since then, scholars, researchers and journalists have descended upon Lynchburg, Tennessee, hoping to learn more about a man who, until then, had appeared as a mere appendage in the story of the country’s most popular whiskey brand.

As a scholar of tourism whose research involves highlighting marginalized populations and counternarratives, I followed these developments with keen interest.

In the fall of 2020, my critical sustainable tourism students created a short documentary, “Uncovering Nearest.” I wanted my students to learn more about Green, since so many voices and faces of enslaved Africans and Black Americans have been silenced or erased from American history textbooks and heritage tourism sites.

Black culinary innovation

Popular media, through shows like Netflix’s “High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America,” have finally started to acknowledge the ways in which Black Americans have contributed to some of America’s most iconic dishes and spirits.

For example, James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved chef, traveled with Jefferson in 1784 to France, where he trained in French cooking at the highest culinary level. He ended up being instrumental in introducing legendary dishes like macaroni and cheese, ice cream and French fries to the United States.

James Hemings eventually trained his younger brother, Peter, to take his place. In the fall of 1813, Peter Hemings learned brewing, and it’s likely that he became the the first Black person in America to be professionally trained as a craft beer brewer.

Neither James nor Peter Hemings was a hobby chef or leisure brewer; this was their forced way of life. And the enslaved people who crafted new dishes didn’t set out to change American cuisine. They simply needed to make do with what little they had.

Enslaved cooks were responsible for introducing ingredients and the know-how of such complex and labor-intensive dishes as oyster stew, gumbo, jambalaya and fried fish. However, their voices, names and creations were routinely left out of cookbooks, where their white owners received the credit and the acclaim.

Nearest’s legacy unveiled

Now one name – Nearest Green – has become synonymous with whiskey.

The New York Times article from 2016 inspired author and entrepreneur Fawn Weaver to set out on a quest to reveal Nearest Green’s full story – what ended up as a 12-month research project involving more than 20 historians, archivists, archaeologists, conservators and genealogists.

Thanks to her work, a fuller picture of Green’s legacy has emerged.

Around the mid-1800s, Green’s enslavers were a firm known as Landis & Green, who “leant out” Nearest Green for a fee to local preacher, the Rev. Dan Call. This was typical in an era in which enslaved men were commonly involved in the making of spirits due to its reputation as dangerous, dirty work.

Nearest was known as a skilled distiller who specialized in a process known as sugar maple charcoal filtering – also called the Lincoln County Process. This method – which some historians believe was inspired by the techniques of enslaved men and women who had used charcoal to filter their water and purify their foods in West Africa – gave Green’s whiskey a unique smoothness.

Years later, Jack Daniel, a 7-year-old white orphan, was sent to the Call farm to be a chore boy. Eventually, he became Green’s apprentice and was taught the Lincoln County Process, which differentiates bourbon from Tennessee whiskey – making Nearest responsible for the Tennessee whiskey we know today. As Victoria Eady-Butler, Green’s descendant and former employee of Jack Daniel’s Distillery, noted that there would “never have been Jack Daniel’s made without a Green on the property.”

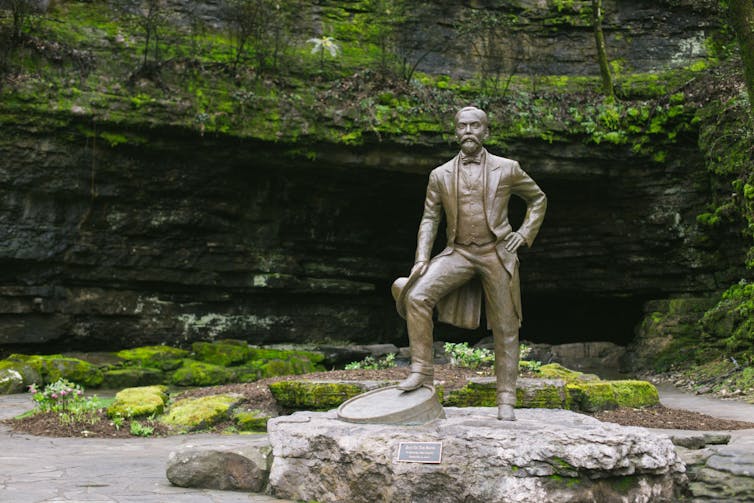

After emancipation, Call sold his distillery to Jack Daniel. Daniel appointed Nearest Green, by then a free man, to be the Jack Daniel Distillery’s first master distiller, and thus the first Black master distiller on record in the United States. Weaver discovered that sometime after 1881, Daniel moved his distillery to its current Cave Spring Hollow location, where several of Green’s children and grandchildren went to work for him.

Kyle Dean Reinford/Picture Alliance via Getty Images

Nearest’s second-born and fourth-born sons, George and Eli, distilled whiskey on the Call Farm alongside Jack Daniel. Although no images of Nearest Green exist, a photograph shows one of his sons, George, sitting next to Jack Daniel.

Altogether, seven generations of Nearest Green’s family have worked for the Jack Daniel Distillery and continue to work there to this day.

A whiskey brand of their own

Jack Daniel and his descendants made a lot of money from their whiskey company over the years. In 1956, the family sold it to Brown-Forman for US$20 million dollars – about $190 million in today’s money.

While Nearest Green and his descendants do appear to have been paid fairly by the Daniel family, they didn’t own any of the distillery – and, consequently, didn’t get any of those millions.

For decades, Nearest Green’s name, legacy and contribution to whiskey were largely unknown to anyone outside Lynchburg, Tennessee – even though, after the Civil War, according to census data, Nearest Green and his family owned sizable plots of land and were wealthier than many white families living in Lynchburg.

Weaver was able to meet Green’s descendants during her research and asked them how they would like to see him honored. They told her that “putting his name on a bottle, letting people know what he did, would be great.”

This gave Weaver the idea to start her own whiskey company that honored Green’s legacy. By 2019 she had raised $40 million from investors to create Uncle Nearest Premium Whiskey. Later that year she opened the Nearest Green Distillery in Shelbyville. Weaver now serves as CEO of the company, with Victoria Eady-Butler, a descendant of Green’s, employed as the distillery’s master blender.

Unearthing and celebrating stories like Green’s is part of a push by scholars and travel companies to expand marketing and storytelling in ways that include overlooked or silenced perspectives.

Stefanie Benjamin, CC BY

In 2020, Nomadness Travel Tribe partnered with Tourism RESET, where I serve as a co-director and research fellow, to publish a report that included both qualitative in-depth interviews and a quantitative survey of more than 5,000 tourists to better understand the travel experiences of Black people and other people of color.

Meanwhile, the Black Travel Alliance, also in partnership with Tourism RESET, recently launched a new timeline and website, History Of Black Travel, which seeks to educate the public on “how the African diaspora traveled to every part of the Earth.”

Ideally these efforts will create spaces for dialogue around difficult topics like race and enslavement while authentically honoring and amplifying the voices and legacies of Black Americans who helped to build the United States.

And hopefully more stories of people like Nearest Green – an accomplished Black man with a rich, nuanced life – will emerge.![]()

Stefanie Benjamin, Assistant Professor of Retail, Hospitality, and Tourism Management, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.