“I am not ashamed of my grandparents for having been slaves. I am only ashamed of myself for having at one time been ashamed.” — Ralph Ellison

In an email, Laurie Endicott Thomas, the author of “No More Measles: The Truth About Vaccines and Your Health,” said the most important person in the history of American medicine was an enslaved African whose real name we do not know. “His slave name was Onesimus, which means useful in Latin. The Biblical Onesmius ran away from slavery but was persuaded to return to his master,” Thomas said.

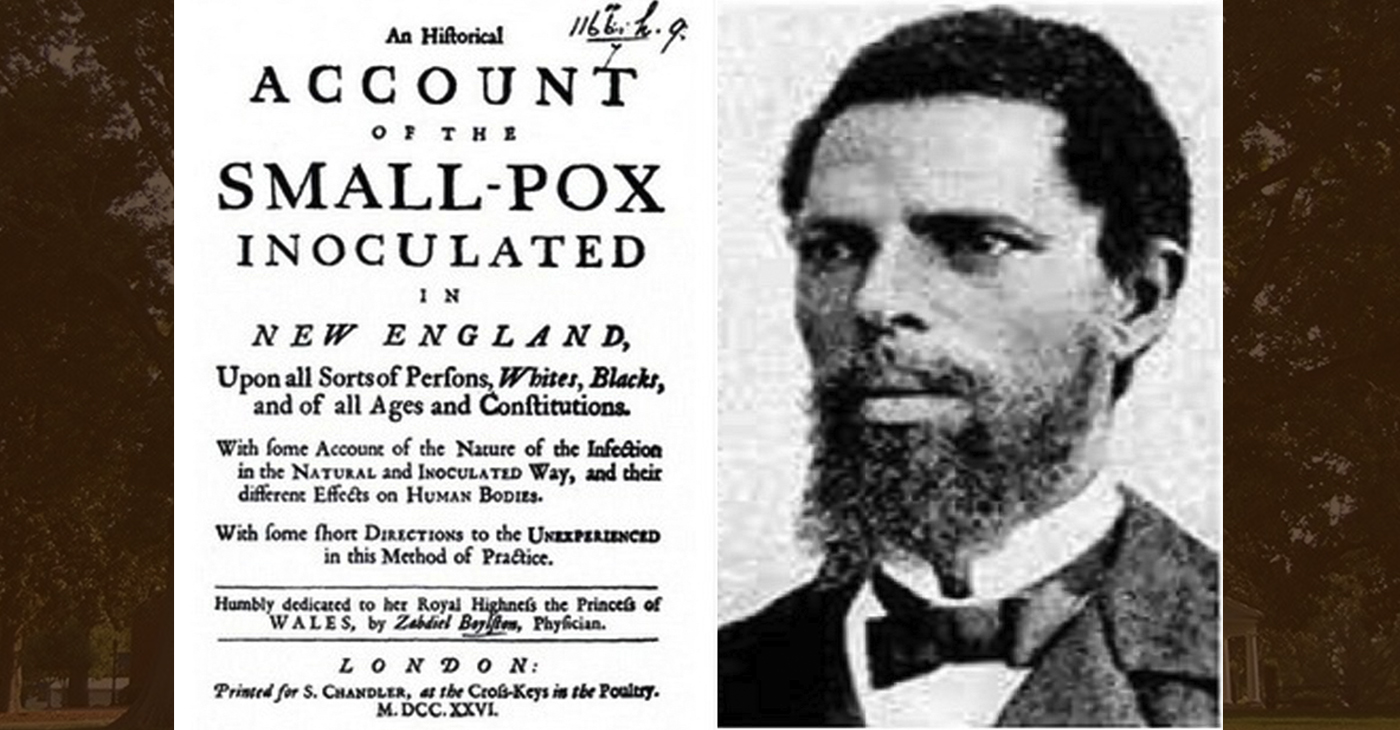

“The African-American Onesimus was the person who introduced the practice of immunization against smallpox to North America. This immunization process was called variolation because it involved real smallpox. Variolation led to sharp decreases in the death rate from smallpox and an important decrease in overall death rates,” she said.

Thomas’ thoughts jelled with a Harvard University study and a Boston WGHB report from 2016 which noted that after 150 years, Jack Daniels finally came clean that its famed whisky recipe came courtesy of a Tennessee slave. “This is – of course – by no means the only example of a slave’s contribution to American industry and culture being, at worst, stolen and, at best, minimized or completely forgotten. There was Baltimore slave Benjamin Bradley’s steam engine.

“And a Mississippi slave known only as Ned’s cotton scraper. And then, there was Boston’s own Onesimus. Cotton Mather was Onesimus’ owner. “Mather was interested in his slave whom he called Onesimus, which was the name of a slave belonging to St. Paul in the Bible,” explained Widmer. Described by Mather as a “pretty intelligent fellow,” Onesimus had a small scar on his arm, which he explained to Mather was why he had no fear of the era’s single deadliest disease: smallpox.

“Mather was fascinated by what Onesimus knew of inoculation practices back in Africa where he was from,” said Widmer.

“Our way of thinking of the world is often not accurate,” said Widmer. “For centuries Europe was behind other parts of the world in its medical practices.”

Bostonians like Mather were no strangers to smallpox. Outbreaks in 1690 and 1702 had devastated the colonial city. And Widmer says Mather took a keen interest in Onesimus’ understanding of how the inoculation was done. “They would take a small amount of a similar disease, sometimes cowpox, and they would open a cut and put a little drop of the disease into the bloodstream,” explained Widmer. “And they knew that that was a way of developing resistance to it,” he said.

The Harvard University report further cemented what Onesimus accomplished after a smallpox outbreak once again gripped Boston in 1721.

Mather is largely credited with introducing inoculation to the colonies and doing a great deal to promote the use of this method as standard for smallpox prevention during the 1721 epidemic, Harvard authors wrote.

Then, they noted: Mather is believed to have first learned about inoculation from his West African slave Onesimus, writing, “he told me that he had undergone the operation which had given something of the smallpox and would forever preserve him from it, adding that was often used in West Africa.’’ After confirming this account with other West African slaves and reading of similar methods being performed in Turkey, Mather became an avid proponent of inoculation.

When the 1721 smallpox epidemic struck Boston, Mather took the opportunity to campaign for the systematic application of inoculation.

The scourge of slavery would continue in Massachusetts for another 60 years, but as for the man whose knowledge sparked the breakthrough… “Onesimus was recognized as the savior of a lot of Bostonians and was admired and then was emancipated,” Widmer said. “Onesimus was a hero. He gave of his knowledge freely and was himself freed.”